Fat in Urine: Causes and What to Do

Fat in urine is often characterized by an oily texture or buoyancy. These are the informal telltale signs, as the relevant urine tests are the only ones that can confirm or deny the presence of fat in urine. If you have detected the first signs, we’ll show you some possible causes of fat in urine and what to do about it.

Urine fat can have multiple catalysts. We reiterate that the relevant tests and the evaluation of a professional are the only way to diagnose its causes; the information that we give is only referential.

Main causes of fat in urine

Urine is a general indicator of a person’s health. This is because bodily changes cause direct changes in its color, smell, and texture. Below we’ll analyze the main causes of fat in urine, and we’ll do so taking the contributions of scientists as a reference.

1. Ketosis

The metabolic process by which the body processes fat for energy is called ketosis. Glucose is the body’s main source of energy, but it’s also capable of processing fat. As a byproduct of this metabolic process, ketones are produced, which can be detected in the breath, blood, and urine.

Mild ketosis isn’t a problem, but very high levels can cause an emergency. The main cause of this metabolic change is exercise and diet. Diets with little carbohydrate content and the combination with intense exercise provoke this metabolic change (in fact, fat or weight is lost because of it). Other of its possible catalysts are the following:

- Eating disorders (such as anorexia and bulimia)

- Diabetes

- Continuous diarrhea and vomiting

- Pregnancy

- Some digestive disorders

- Excessive alcohol dependence

- Starvation (absence of food for prolonged periods)

The presence of ketones in the urine can be detected with a urine test. If this is accompanied by nausea, vomiting, shortness of breath, drowsiness, and confusion, it will often indicate a moderate or severe complication.

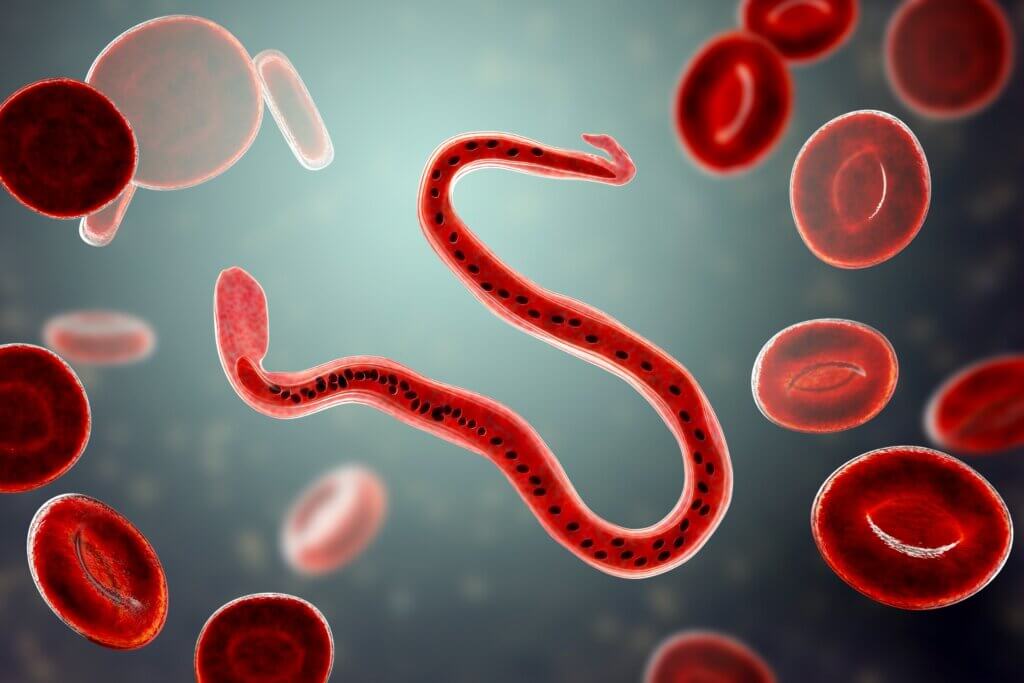

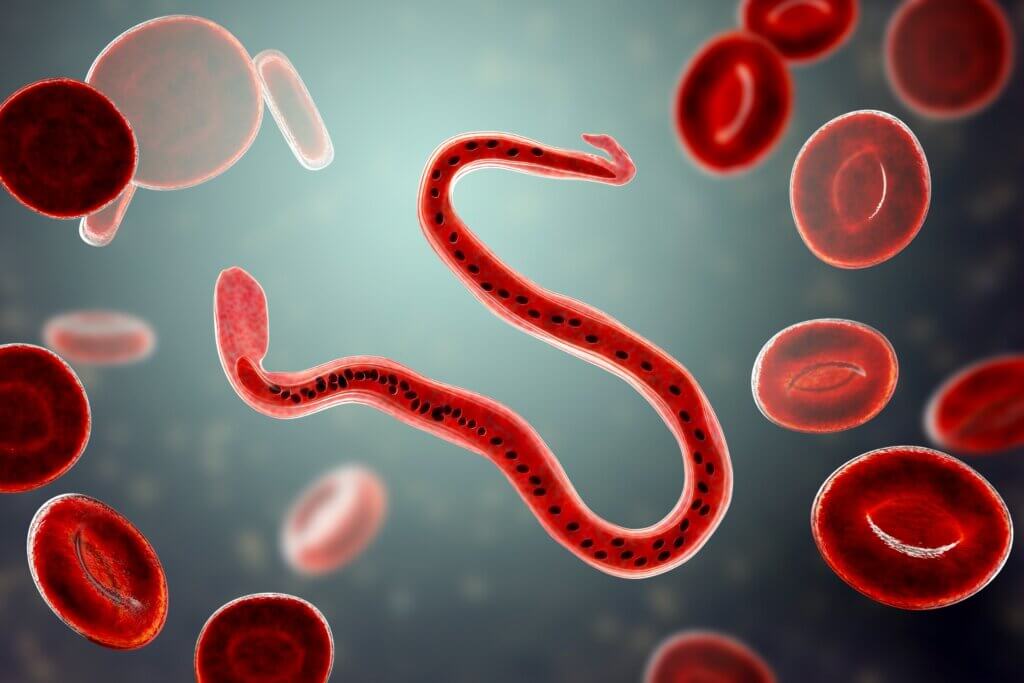

2. Chyluria

Also known as chylous urine, it’s a medical condition characterized by milky-appearing urine. This is due to the appearance of chyle, a body fluid made up of emulsified fats, free fatty acids, and lymph. Experts classify chyluria into two types: parasitic and non-parasitic.

Up to 95% of parasitic causes are attributed to W. bancrofti infection. Some birth defects, kidney damage, genetic problems, and tumors are among the non-parasitic causes. Beyond the oily texture, the milky or whitish color is its main distinguishing mark.

3. Lipiduria

Lipiduria is the term used to refer to lipids in the urine. Most cases are a consequence of the nephrotic syndrome. This condition causes the kidneys to expel more protein in the urine than they should. Its causes are very diverse, although the main culprits are focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and minimal change disease.

As experts point out, nephrotic syndrome can lead to complications, including anemia, hypovolemic crisis, cardiovascular diseases, thromboembolism, infections and kidney failure. Its symptoms are very foamy urine, fluid retention, loss of appetite, and fatigue.

Treatment for fat in urine

In general, the presence of fat in urine should be analyzed according to the patient’s context to determine the cause. People should be aware of the following symptoms, which often indicate a process that requires medical attention:

- Pain when urinating

- Abdominal pain

- Continuous sleepiness

- Fatigue and tiredness

- Blood in the urine

- Urine highly concentrated in color and odor

- Confusion

- Very frequent urination

Whatever the case, the ideal step is to perform a urine test to rule out or confirm any of the conditions indicated. Based on the results, the specialist will determine the best treatment, or suggest some changes in daily habits, to ensure healthy and safe habits in your day-to-day life.

Fat in urine is often characterized by an oily texture or buoyancy. These are the informal telltale signs, as the relevant urine tests are the only ones that can confirm or deny the presence of fat in urine. If you have detected the first signs, we’ll show you some possible causes of fat in urine and what to do about it.

Urine fat can have multiple catalysts. We reiterate that the relevant tests and the evaluation of a professional are the only way to diagnose its causes; the information that we give is only referential.

Main causes of fat in urine

Urine is a general indicator of a person’s health. This is because bodily changes cause direct changes in its color, smell, and texture. Below we’ll analyze the main causes of fat in urine, and we’ll do so taking the contributions of scientists as a reference.

1. Ketosis

The metabolic process by which the body processes fat for energy is called ketosis. Glucose is the body’s main source of energy, but it’s also capable of processing fat. As a byproduct of this metabolic process, ketones are produced, which can be detected in the breath, blood, and urine.

Mild ketosis isn’t a problem, but very high levels can cause an emergency. The main cause of this metabolic change is exercise and diet. Diets with little carbohydrate content and the combination with intense exercise provoke this metabolic change (in fact, fat or weight is lost because of it). Other of its possible catalysts are the following:

- Eating disorders (such as anorexia and bulimia)

- Diabetes

- Continuous diarrhea and vomiting

- Pregnancy

- Some digestive disorders

- Excessive alcohol dependence

- Starvation (absence of food for prolonged periods)

The presence of ketones in the urine can be detected with a urine test. If this is accompanied by nausea, vomiting, shortness of breath, drowsiness, and confusion, it will often indicate a moderate or severe complication.

2. Chyluria

Also known as chylous urine, it’s a medical condition characterized by milky-appearing urine. This is due to the appearance of chyle, a body fluid made up of emulsified fats, free fatty acids, and lymph. Experts classify chyluria into two types: parasitic and non-parasitic.

Up to 95% of parasitic causes are attributed to W. bancrofti infection. Some birth defects, kidney damage, genetic problems, and tumors are among the non-parasitic causes. Beyond the oily texture, the milky or whitish color is its main distinguishing mark.

3. Lipiduria

Lipiduria is the term used to refer to lipids in the urine. Most cases are a consequence of the nephrotic syndrome. This condition causes the kidneys to expel more protein in the urine than they should. Its causes are very diverse, although the main culprits are focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and minimal change disease.

As experts point out, nephrotic syndrome can lead to complications, including anemia, hypovolemic crisis, cardiovascular diseases, thromboembolism, infections and kidney failure. Its symptoms are very foamy urine, fluid retention, loss of appetite, and fatigue.

Treatment for fat in urine

In general, the presence of fat in urine should be analyzed according to the patient’s context to determine the cause. People should be aware of the following symptoms, which often indicate a process that requires medical attention:

- Pain when urinating

- Abdominal pain

- Continuous sleepiness

- Fatigue and tiredness

- Blood in the urine

- Urine highly concentrated in color and odor

- Confusion

- Very frequent urination

Whatever the case, the ideal step is to perform a urine test to rule out or confirm any of the conditions indicated. Based on the results, the specialist will determine the best treatment, or suggest some changes in daily habits, to ensure healthy and safe habits in your day-to-day life.

- Park SJ, Shin JI. Complications of nephrotic syndrome [published correction appears in Korean J Pediatr. 2012 Apr;55(4):151]. Korean J Pediatr. 2011;54(8):322-328.

- Stainer V, Jones P, Juliebø SØ, Beck R, Hawary A. Chyluria: what does the clinician need to know?. Ther Adv Urol. 2020;12:1756287220940899. Published 2020 Jul 16.

Este texto se ofrece únicamente con propósitos informativos y no reemplaza la consulta con un profesional. Ante dudas, consulta a tu especialista.