Hashimoto's Disease: Symptoms, Causes and Treatment

Escrito y verificado por el biólogo Samuel Antonio Sánchez Amador

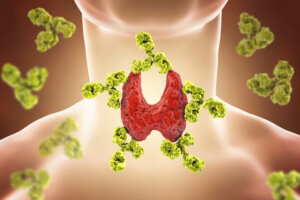

Hashimoto’s disease (also known as chronic thyroiditis) is an autoimmune disease that causes autoantibody-mediated destruction of the thyroid gland. Its incidence fluctuates between 0.3 and 1.5 cases per 1,000 people per year and affects approximately 2% of the world population.

The name of this pathology comes from the Japanese doctor Hakaru Hashimoto, who first described the pathology in 1912. If you want to know everything about this disease, including its symptoms, causes, and possible treatments, read on.

About the thyroid gland

Before describing the disease, it’s best to first review the structures it affects. The thyroid is an endocrine gland, which means that it releases hormones into the blood to travel to the target organ. It’s located in the area of the laryngeal prominence in the neck, under the thyroid cartilage, and supported on the trachea.

This endocrine organ weighs about 15-30 grams (around 1 oz) in adults and has a characteristic butterfly shape. Its main function is the production and release of the hormones T3 and T4 into the bloodstream, which influence almost all of our cells and regulate human metabolism. We’re now going to have a closer look.

T3 hormone or triiodothyronine

T3 affects almost all physiological processes in the body, as it modulates growth, development, metabolism, body temperature, and heart rate, among many other things. As indicated by the Spanish Association of Thyroid Cancer (AECAT), this hormone arises after the union of monoiodotyrosine (MIT, T1) and diiodotyrosine (DIT, T2)

Triiodotyrosine T3 (3 iodine radicals): T1 (one iodine radical) + T2 (2 iodine radicals).

T3 production is activated by thyrotropin (TSH), also known as thyroid-stimulating hormone, which is produced in the pituitary gland. In turn, the pituitary is activated by HRT, another hormone from the hypothalamus. Remember this information, as it will be of great importance in future sections of this article.

T4 hormone or thyroxine

In the case of T4, this is a prohormone secreted by the thyroid that is transformed into triiodothyronine by the action of TSH. Thyroxine is the most abundant form in circulating blood, however, T3 is the one with the highest functionality in the body.

T4 is the reserve form of T3, since the latter quadruples it in functionality. The process of converting T4 to T3 takes place in the thyroid itself and other parts of the body.

We know that all this terminology is a bit confusing, but it’s necessary in order to understand Hashimoto’s disease. Without further ado, we’re now going to address the pathology itself.

Causes of Hashimoto’s disease

According to the Mayo Clinic , Hashimoto’s disease is autoimmune in nature. The immune system (which protects the body) doesn’t recognize the thyroid and, therefore, begins to generate antibodies to attack its tissues. This causes inflammation in the gland and a drastic reduction in its functional capacity.

The two antibodies that are usually designated to detect the disease are thyroglobulin (TgAb) and thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies. The latter attack a thyroid enzyme that plays an essential role in the production of thyroid hormones.

As the NIH indicates, the scientific world isn’t entirely sure why this autoimmune rejection occurs in the first place. However, it’s suspected that this type of disorder arises from a combination of genetics and an external trigger, such as a viral infection.

When this pathology occurs, lymphocytes accumulate in the thyroid gland. These synthesize autoantibodies that attack the gland tissues.

Diseases associated with its appearance

According to sources already cited, women have up to 8 times more risk than men of suffering from Hashimoto’s disease. Also, although it can appear at any age, people between 40 and 60 years of age are more susceptible. Up to 2% of the world’s population can develop it, which is 2 out of every 100 inhabitants.

In addition, the probability of getting this illness increases if other members of the family have it. Here are three autoimmune diseases that are sometimes associated with its appearance:

- Addison’s disease

- Celiac disease

- Diabetes type 1

However, the appearance of these diseases doesn’t necessarily mean that the patient is going to suffer from Hashimoto’s disease in the future. As we said earlier, there’s still much to understand as far as its appearance is concerned.

Symptoms of Hashimoto’s disease

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is the leading cause of hypothyroidism in regions where iodine intake is adequate. This is the key term in the disease we’re talking about today: hypothyroidism.

The lymphocyte attack on the thyroid gland causes it to produce fewer thyroid hormones and, consequently, it gradually fails and the thyroid is considered underactive. This gives way to the hypothyroidism known to all of us, that is, the lack of T3 and t4 hormones in the body.

According to the medical portal Thyroid.org there’s no single clinical sign of Hashimoto’s disease. In addition, because its progression is slow, patients may not notice any signs during the early stages of development. As the condition progresses, these symptoms become more and more apparent:

- Fatigue, laziness, and depression

- Puffy face, pale skin, and brittle nails

- Loss of hair

- Increase in the size of the tongue

- Muscle pain, tenderness, and stiffness

- Excessive or prolonged menstrual bleeding

- Unexplained weight gain

- Constipation

- Difficulties thinking or achieving a certain degree of concentration

In extreme situations, this type of hypothyroidism can lead to heart failure, myxedema, respiratory failure, and a coma with loss of consciousness. As indicated by the Navarra University Clinic (CUN), the mortality rate at this point is very high.

Myxedema coma has a mortality rate in hypothyroid patients of 30% if not treated promptly.

Hashimoto’s disease diagnosis

When the patient comes to the doctor with symptoms of hypothyroidism, one of the main suspicions during the physical examination is the presence of goiter, that is, an enlarged thyroid. This anatomical sign is painless in many cases, but can cause swallowing and breathing difficulties.

If the medical professional believes that the individual has Hashimoto’s disease, different laboratory tests are used. The National Library of Medicine of the United States exposes the most important ones, and we collect their particularities in the following lines.

1. T4 test

T4 is the main hormone produced in the thyroid. For this reason, the amount of free T4 in the blood can indicate the functionality of the gland. This test is simple to perform, as only a sample of the patient’s blood is required. A typical normal range is 0.9 to 2.3 nanograms per deciliter, or 12 to 30 picomoles per liter.

2. T3 total

This is very similar to the previous point, but, in this case, the amount of the T3 hormone in the blood is quantified. The normal range of values is 60 to 180 nanograms per deciliter of blood in the normal form and 130 to 450 picograms per deciliter in the free form.

3. Autoantibody test

In this case, it’s a question of looking for circulating antibodies that are associated with the destruction of the thyroid gland. In general, the presence of thyroglobulin and thyroid peroxidase antibodies explain the patient’s symptoms.

Treatment of Hashimoto’s disease

We’re nearing the end of the article, but this is perhaps the most important part of everything we’ve explained so far. It’s time to explore the clinical and domestic treatment necessary to address Hashimoto’s disease. The Kids Health portal and other sources already cited tell us what to do about this pathology.

Administration of synthetic hormones

The treatment of hypothyroidism caused by Hashimoto’s disease involves the replacement of the thyroid’s production. The most effective way to compensate for this dysfunction is by prescribing synthetic analogs to the T4 hormone, as it’s transformed into T3 naturally within the body and its life is longer.

Commercial preparations of these drugs (Levoxyl ® or Synthroid ® ) contain about 50 or 100 micrograms of the compound per tablet. The oral dose is given only once a day on an empty stomach, but the appropriate amount depends on the individual response anyway.

Continuous monitoring of the patient is necessary until their blood thyroid hormone levels return to normal.

Is it necessary to perform a combination of hormones?

Finding an answer to this question is a controversial topic in science. Although there are some specialists who are in favor of substituting part of the T4 dose for T3, much research indicates that this doesn’t report any clear benefit.

On the other hand, direct administration of T3 (Cytomel) could be positive for patients who have had the entire thyroid removed. Studies on this issue are still under development, and there’s still no clear answer as yet.

A complex and important disease

We’ve given you an extensive insight into Hashimoto’s disease, but it won’t hurt to give you a final outline to bring all the points together.

- The thyroid gland participates in the synthesis of the hormones T3 and T4, essential for almost all the physiological processes in human beings.

- Hashimoto’s disease occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks thyroid tissue. This causes a decrease in the functionality of the thyroid and, therefore, hypothyroidism.

- Hypothyroidism manifests itself with a series of nonspecific symptoms that get worse over time. Goiter is one of the most obvious.

- The cause of Hashimoto’s disease is not fully known, but it’s believed to have both a genetic and an environmental component.

- The diagnosis is made based on a series of blood tests.

- Treatment consists of the administration of synthetic analogues to thyroid hormones.

With this series of key points, the bases of the pathology that concerns us here are clear. Hashimoto’s disease is the leading cause of hypothyroidism in high-income countries, but, fortunately, its approach is straightforward if drugs are available in the right doses.

Hashimoto’s disease (also known as chronic thyroiditis) is an autoimmune disease that causes autoantibody-mediated destruction of the thyroid gland. Its incidence fluctuates between 0.3 and 1.5 cases per 1,000 people per year and affects approximately 2% of the world population.

The name of this pathology comes from the Japanese doctor Hakaru Hashimoto, who first described the pathology in 1912. If you want to know everything about this disease, including its symptoms, causes, and possible treatments, read on.

About the thyroid gland

Before describing the disease, it’s best to first review the structures it affects. The thyroid is an endocrine gland, which means that it releases hormones into the blood to travel to the target organ. It’s located in the area of the laryngeal prominence in the neck, under the thyroid cartilage, and supported on the trachea.

This endocrine organ weighs about 15-30 grams (around 1 oz) in adults and has a characteristic butterfly shape. Its main function is the production and release of the hormones T3 and T4 into the bloodstream, which influence almost all of our cells and regulate human metabolism. We’re now going to have a closer look.

T3 hormone or triiodothyronine

T3 affects almost all physiological processes in the body, as it modulates growth, development, metabolism, body temperature, and heart rate, among many other things. As indicated by the Spanish Association of Thyroid Cancer (AECAT), this hormone arises after the union of monoiodotyrosine (MIT, T1) and diiodotyrosine (DIT, T2)

Triiodotyrosine T3 (3 iodine radicals): T1 (one iodine radical) + T2 (2 iodine radicals).

T3 production is activated by thyrotropin (TSH), also known as thyroid-stimulating hormone, which is produced in the pituitary gland. In turn, the pituitary is activated by HRT, another hormone from the hypothalamus. Remember this information, as it will be of great importance in future sections of this article.

T4 hormone or thyroxine

In the case of T4, this is a prohormone secreted by the thyroid that is transformed into triiodothyronine by the action of TSH. Thyroxine is the most abundant form in circulating blood, however, T3 is the one with the highest functionality in the body.

T4 is the reserve form of T3, since the latter quadruples it in functionality. The process of converting T4 to T3 takes place in the thyroid itself and other parts of the body.

We know that all this terminology is a bit confusing, but it’s necessary in order to understand Hashimoto’s disease. Without further ado, we’re now going to address the pathology itself.

Causes of Hashimoto’s disease

According to the Mayo Clinic , Hashimoto’s disease is autoimmune in nature. The immune system (which protects the body) doesn’t recognize the thyroid and, therefore, begins to generate antibodies to attack its tissues. This causes inflammation in the gland and a drastic reduction in its functional capacity.

The two antibodies that are usually designated to detect the disease are thyroglobulin (TgAb) and thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies. The latter attack a thyroid enzyme that plays an essential role in the production of thyroid hormones.

As the NIH indicates, the scientific world isn’t entirely sure why this autoimmune rejection occurs in the first place. However, it’s suspected that this type of disorder arises from a combination of genetics and an external trigger, such as a viral infection.

When this pathology occurs, lymphocytes accumulate in the thyroid gland. These synthesize autoantibodies that attack the gland tissues.

Diseases associated with its appearance

According to sources already cited, women have up to 8 times more risk than men of suffering from Hashimoto’s disease. Also, although it can appear at any age, people between 40 and 60 years of age are more susceptible. Up to 2% of the world’s population can develop it, which is 2 out of every 100 inhabitants.

In addition, the probability of getting this illness increases if other members of the family have it. Here are three autoimmune diseases that are sometimes associated with its appearance:

- Addison’s disease

- Celiac disease

- Diabetes type 1

However, the appearance of these diseases doesn’t necessarily mean that the patient is going to suffer from Hashimoto’s disease in the future. As we said earlier, there’s still much to understand as far as its appearance is concerned.

Symptoms of Hashimoto’s disease

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is the leading cause of hypothyroidism in regions where iodine intake is adequate. This is the key term in the disease we’re talking about today: hypothyroidism.

The lymphocyte attack on the thyroid gland causes it to produce fewer thyroid hormones and, consequently, it gradually fails and the thyroid is considered underactive. This gives way to the hypothyroidism known to all of us, that is, the lack of T3 and t4 hormones in the body.

According to the medical portal Thyroid.org there’s no single clinical sign of Hashimoto’s disease. In addition, because its progression is slow, patients may not notice any signs during the early stages of development. As the condition progresses, these symptoms become more and more apparent:

- Fatigue, laziness, and depression

- Puffy face, pale skin, and brittle nails

- Loss of hair

- Increase in the size of the tongue

- Muscle pain, tenderness, and stiffness

- Excessive or prolonged menstrual bleeding

- Unexplained weight gain

- Constipation

- Difficulties thinking or achieving a certain degree of concentration

In extreme situations, this type of hypothyroidism can lead to heart failure, myxedema, respiratory failure, and a coma with loss of consciousness. As indicated by the Navarra University Clinic (CUN), the mortality rate at this point is very high.

Myxedema coma has a mortality rate in hypothyroid patients of 30% if not treated promptly.

Hashimoto’s disease diagnosis

When the patient comes to the doctor with symptoms of hypothyroidism, one of the main suspicions during the physical examination is the presence of goiter, that is, an enlarged thyroid. This anatomical sign is painless in many cases, but can cause swallowing and breathing difficulties.

If the medical professional believes that the individual has Hashimoto’s disease, different laboratory tests are used. The National Library of Medicine of the United States exposes the most important ones, and we collect their particularities in the following lines.

1. T4 test

T4 is the main hormone produced in the thyroid. For this reason, the amount of free T4 in the blood can indicate the functionality of the gland. This test is simple to perform, as only a sample of the patient’s blood is required. A typical normal range is 0.9 to 2.3 nanograms per deciliter, or 12 to 30 picomoles per liter.

2. T3 total

This is very similar to the previous point, but, in this case, the amount of the T3 hormone in the blood is quantified. The normal range of values is 60 to 180 nanograms per deciliter of blood in the normal form and 130 to 450 picograms per deciliter in the free form.

3. Autoantibody test

In this case, it’s a question of looking for circulating antibodies that are associated with the destruction of the thyroid gland. In general, the presence of thyroglobulin and thyroid peroxidase antibodies explain the patient’s symptoms.

Treatment of Hashimoto’s disease

We’re nearing the end of the article, but this is perhaps the most important part of everything we’ve explained so far. It’s time to explore the clinical and domestic treatment necessary to address Hashimoto’s disease. The Kids Health portal and other sources already cited tell us what to do about this pathology.

Administration of synthetic hormones

The treatment of hypothyroidism caused by Hashimoto’s disease involves the replacement of the thyroid’s production. The most effective way to compensate for this dysfunction is by prescribing synthetic analogs to the T4 hormone, as it’s transformed into T3 naturally within the body and its life is longer.

Commercial preparations of these drugs (Levoxyl ® or Synthroid ® ) contain about 50 or 100 micrograms of the compound per tablet. The oral dose is given only once a day on an empty stomach, but the appropriate amount depends on the individual response anyway.

Continuous monitoring of the patient is necessary until their blood thyroid hormone levels return to normal.

Is it necessary to perform a combination of hormones?

Finding an answer to this question is a controversial topic in science. Although there are some specialists who are in favor of substituting part of the T4 dose for T3, much research indicates that this doesn’t report any clear benefit.

On the other hand, direct administration of T3 (Cytomel) could be positive for patients who have had the entire thyroid removed. Studies on this issue are still under development, and there’s still no clear answer as yet.

A complex and important disease

We’ve given you an extensive insight into Hashimoto’s disease, but it won’t hurt to give you a final outline to bring all the points together.

- The thyroid gland participates in the synthesis of the hormones T3 and T4, essential for almost all the physiological processes in human beings.

- Hashimoto’s disease occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks thyroid tissue. This causes a decrease in the functionality of the thyroid and, therefore, hypothyroidism.

- Hypothyroidism manifests itself with a series of nonspecific symptoms that get worse over time. Goiter is one of the most obvious.

- The cause of Hashimoto’s disease is not fully known, but it’s believed to have both a genetic and an environmental component.

- The diagnosis is made based on a series of blood tests.

- Treatment consists of the administration of synthetic analogues to thyroid hormones.

With this series of key points, the bases of the pathology that concerns us here are clear. Hashimoto’s disease is the leading cause of hypothyroidism in high-income countries, but, fortunately, its approach is straightforward if drugs are available in the right doses.

- Las hormonas tiroideas: que son y para qué sirven, AECAT. Recogido a 4 de marzo en https://www.aecat.net/2015/07/16/las-hormonas-tiroideas-que-son-y-para-que-sirven/

- Enfermedad de Hashimoto, Clínica Mayo. Recogido a 4 de marzo en https://www.mayoclinic.org/es-es/diseases-conditions/hashimotos-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20351855

- Enfermedad de Hashimoto, NIH. Recogido a 4 de marzo en https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/informacion-de-la-salud/enfermedades-endocrinas/enfermedad-de-hashimoto

- Enfermedad de Hashimoto, Thyroid.org. Recogido a 4 de marzo en http://www.thyroid.org/wp-content/uploads/patients/brochures/espanol/tiroiditis_de_hashimoto.pdf

- Tiroiditis de Hashimoto, CUN. Recogido a 4 de marzo en https://www.cun.es/enfermedades-tratamientos/enfermedades/tiroiditis-hashimoto

- Tiroiditis crónica, Medlineplus.gov. Recogido a 4 de marzo en https://medlineplus.gov/spanish/ency/article/000371.htm#:~:text=Es%20una%20afecci%C3%B3n%20causada%20por,conoce%20como%20Enfermedad%20de%20Hashimoto.

- Hipotiroidismo y enfermedad de Hashimoto, KidsHealth. Recogido a 4 de marzo en https://kidshealth.org/es/parents/hypothyroidism-esp.html#:~:text=Los%20niveles%20elevados%20de%20estos,la%20peroxidasa%20tiroidea%20(TPO).

Este texto se ofrece únicamente con propósitos informativos y no reemplaza la consulta con un profesional. Ante dudas, consulta a tu especialista.